Yet Another Group of Birds Named for People

This is next in a series of articles I am writing about the folks that have birds named for them. As you probably have heard, AOS plans to remove these names in the future and bury the history, good and bad, of the hobby we love. This is my effort to tell you a bit of that history before you have to dig farther to find it.

Abert’s Towhee

One of the four North American towhees, Abert’s is restricted to a small range in the southwestern US along brushy riparian habitats in the Lower Sonoran Desert. Its name commemorates American ornithologist James William Abert (1820-1897). Abert was born in New Jersey and graduated from West Point in 1842.

Abert enlisted in the Corps of Topographical Engineers and, in 1843, joined several expeditions into the west, including John Fremont’s third expedition, and illustrated these expeditions’ reports with his sketches. In 1846, he was sent west to join the army of General Kearney in the war against Mexico, returning to Fort Leavenworth the following year. It was during this time that he collected a new species of bird, which was named in his honor.

During the Civil War, he served on the staffs of Robert Patterson, Nathanial Banks, and Quincy Gilmore. He was wounded during the Maryland Campaign and retired from the Army in June 1864. After the Civil War, he became a professor of English literature, mathematics, and drawing at the University of Missouri and, later, a professor of civil engineering, applied mathematics, and engineering drawing at the Missouri School of Mines and Metallurgy.

Virginia’s Warbler

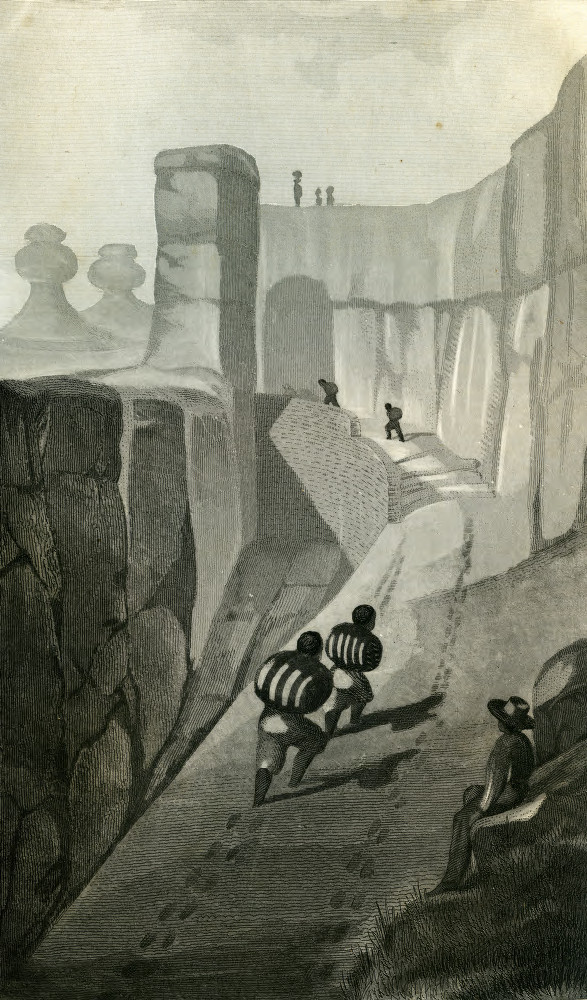

The Trail to Acoma, painting by J.W. Abert,

Virginia Warbler, far from the east coast of the U.S.

Despite what its name may suggest, Virginia’s Warbler is not

actually named after the State of Virginia, which makes sense, as

the birds’ typical range only reaches as far east as the state of

Texas. The bird’s common range is central and southern mountains

of Colorado, central Wyoming and central and western New

Mexico. The bird was named for Virginia Anderson, the wife of an

army surgeon, W.W. Anderson, who discovered the bird at Fort

Burgwin, New Mexico (located 10 miles south of Taos) in 1858.

Later, when Spencer Fullerton Baird, of the Smithsonian

Institution, fully described the bird for science in1860, he honored

Anderson’s wishes and designated Virginia to be both the bird’s

common and scientific name (Oreothlypis virginae).

In case you are wondering, the Virginia Rail was named after the

state of Virginia. Early naturalists first encountered and documented it there.

Sprague’s Pipit

We usually see the American Pipit in our area but, if you head to the short-grass prairie of the American Midwest, you will run into Sprague’s Pipit. This bird was named after botanical illustrator Isaac Sprague.

In 1840, Sprague met John James Audubon, who had admired Sprague’s drawings. In 1843, Sprague served as an assistant to Audubon on an ornithological expedition up the Missouri River, taking measurements and making sketches. Sprague’s Pipit (Anthus spragueii), an uncommon and inconspicuous bird, was discovered on that expedition and named for Sprague. Some of Sprague’s drawings were incorporated into Audubon’s later publications.

In 1845, Sprague met Asa Gray (1810–1888) of Harvard College, considered the most important American botanist of the 19th century, and, over many

years, illustrated several of Gray’s works.

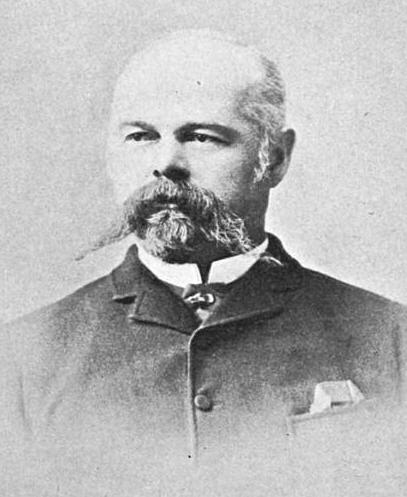

Bendire’s Thrasher

Bendire’s Thrasher is native to southwestern U.S. and northwestern Mexico deserts. Because of its similar coloration and structure to the Curve-billed Thrasher, the two birds are very easy to mistake for one another. The Bendire’sThrasher’s shorter bill is a distinguishing feature when comparing mature birds.

On July 28, 1872, U.S. Army Lieutenant Charles Bendire (1836-1897) was hiking through the brushy desert near Fort Lowell, Arizona. While exploring the desert, Bendire, an avid bird enthusiast, spotted a bird that was unfamiliar to him. Lieutenant Bendire shot the bird, which appeared to be a female thrasher, and sent its remains to the Smithsonian Institution. The specimen was examined by Elliott Coues, who was perplexed as to its species. After several of Coues’s colleagues looked at the bird they believed it was a female Curve-billed Thrasher, but Coues did not agree with their conclusion. Coues believed that the thrasher was a species unknown to science and sought out Bendire for additional information on the bird. Bendire replied to Coues with his affirmation that he alsobelieved that it was a new species.

Lieutenant Bendire soon sent back a second specimen of the thrasher, a male, and details about its habits and eggs, all which were different from those of a Curve-billed Thrasher. Finally convinced, Coues named the new thrasher species Bendire’s Thrasher in the honor of Charles Bendire.

Bendire was born Karl Emil Bender at Konig in Odenwald in the Grand Duchy of Hesse. He emigrated to the U.S. in 1853 and joined the Army in 1854, after changing his name to Charles

Bendire. During Bendire’s service in the army, he was sent to many locations, often isolated, across America, including Virginia, Arizona, Oregon, Washington, and California. It was during these travels across North America that he developed a fondness for all things wild, and particularly birds. He initially sent letters containing his observations to other American naturalists and published them in American naturalist magazines, like the Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club and the American Naturalist.

Bendire’s private collection of 8,000 eggs formed the basis of the

egg collection at the Smithsonian Institution.